“Behold, Lucius,” she said, “moved by your prayer

I come to you—I, the natural mother of all life, the mistress of the elements,

the first child of time, the supreme divinity, the queen of those in

hell, the first among those in heaven, the uniform manifestation of all

the gods and goddesses—I, who govern by my nod the crests of light in

the sky, the purifying wafts of the ocean, and the lamentable silences

of hell—I, whose single godhead is venerated all over the earth under manifold

forms, varying rites, and changing names. Thus, the Phrygians that are

the oldest human stock call me Pessinuntia, Mother of the Gods. The aboriginal

races of Attica call me Cecropian Minerva. The Cyprians in their island-home

call me Paphian Venus. The archer Cretans call me Diana Dictynna. The three-tongued

Sicilians call me Stygian Proserpine. The Eleusinians call me the ancient

goddess Ceres. Some call me Juno. Some call me Bellona. Some call me Hecate.

Some call me Rhamnusia. But those who are enlightened by the earliest rays

of that divinity the sun, the Ethiopians, the Arii, and the Egyptians who

excel in antique lore, all worship me with their ancestral ceremonies

and call me by my true name, Queen Isis...”’

GRAVE'S TRANSLATION (1950) pp. 261-265

‘Not long afterwards I awoke in sudden terror. A dazzling

full moon was rising from the sea. It is at secret hour that the Moon-goddess,

sole sovereign of mankind, is possessed of her greatest power and majesty.

She is the shining deity by whose divine influence not only all beasts, wild

and tame, but all inanimate things as well, are invigorated; whose ebbs

and flows control the rhythm of all bodies whatsoever, whether in the air,

on earth, or below the sea. Of this I was well aware, and therefore resolved

to address the visible image of the goddess, imploring her help; for Fortune

seemed at last to have made up her mind that I had suffered enough and to

be offering me a hope of release.

Jumping up and shaking off my drowsiness, I went down to the sea

to purify myself by bathing in it. Seven times I dipped my head under the

waves—seven, according to the divine philosopher Pythagoras, is a number

that suits all religious occasions—and with joyful eagerness, though tears

were running down my hairy face, I offered this soundless prayer to the supreme

Goddess:

“Blessed Queen of Heaven, whether you are pleased to be known as

Ceres, the original harvest mother who in joy at the finding of your lost

daughter Proserpine abolished the rude acorn diet of our forefathers and

gave them berad raised from the fertile soil of Eleusis; or whether as celestial

Venus, now adored at sea-girt Paphos, who at the time of the first Creation

coupled the sexes in mutual love and so contrived that man should continue

to propagate his kind for ever; or whether as Artemis, the physician sister

of Phoebus Apollo, reliever of the birth pangs of women, and now adored

in the ancient shrine at Ephesus; or whether as dread Proserpine to whom

the owl cries at night, whose triple face is potent against the malice of

ghosts, keeping them imprisoned below earth; you who wander through many

sacred groves and are propitiated with many different rites—you whose womanly

light illumines the walls of every city, whose misty radiance nurses the

happy seeds under the soil, you who control the wandering course of the

sun and the very power of his rays—I beseech you, by whatever name, in whatever

aspect, with whatever ceremonies you deign to be invoked, have mercy on

me in my extreme distress, restore my shattered fortune, grant me repose

and peace after this long sequence of miseries. End my sufferings and perils,

rid me of this hateful four-footed disguise, return me to my family, make

me Lucius once more. But if I have offended some god of unappeasable cruelty

who is bent on making life impossible for me, at least grant me one sure

gift, the gift of death.”

When I had finished my prayer and poured out the full bitterness

of my oppressed heart, I returned to my sandy hollow, where once more sleep

overcame me. I had scarcely closed my eyes before the apparition of a woman

began to rise from the middle of the sea with so lovely a face that the gods

themselves would have fallen down in adoration of it. First the head, then

the whole shining body gradually emerged and stood before me poised on the

surface of the waves. Yes, I will try to describe this transcendent vision,

for though human speech is poor and limited, the Goddess herself will perhaps

inspire me with poetic imagery sufficient to convey some slight inkling

of what I saw.

Her long thick hair fell in tapering ringlets on her lovely

neck, and was crowned with an intricate chaplet in which was woven every

kind of flower. Just above her brow shone a round disc, like a mirror, or

like the bright face of the moon, which told me who she was. Vipers rising

from the left-hand and right-hand partings of her hair supported this disc,

with cars of corn bristling beside them. Her many-colored robe was of finest

linen; part was glistening white, part crocus-yellow, part glowing red and

along the entire hem a woven bordure of flowers and fruit clung swaying in

the breeze. But what aught and held my eye more than anything else was the

deep black luster of her mantle. She wore it slung across her body from the

right hip to the left shoulder, where it was caught in a knot resembling the

boss of a shield; but part of it hung in innumerable folds, the tasseled fringe

quivering. It was embroidered with glittering stars on the hem and everywhere

else, and in the middle beamed a full and fiery moon.

In her right hand she held a bronze rattle, of the sort used

to frighten away the God of the Sirocco; its narrow rim was curved like a

sword-kit and three little rods, which sang shrilly when she shook the handle,

passed horizontally through it. A boat-shaped gold dish hung from her left

hand, and along the upper surface of the handle writhed an asp witch pulled

throat and head raised ready to strike. On her divine feet were slippers

of palm leaves, the emblem of victory.

All the perfumes of Arabia floated into my nostrils as the

Goddess deigned to address me: “You see me here, Lucius, in answer to your

prayer. I am Nature, the universal Mother, mistress of all the elements,

primordial child of time, sovereign of all things spiritual, queen of the

dead, queen also of the immortals, the single manifestation of all gods and

goddesses that are.

My nod governs the shining heights of Heaven, the wholesome

sea-breezes the lamentable silences of the world below. Though I am worshipped

in many aspects, known by countless names, and propitiated with all manner

of different rites, yet the whole round earth venerates me.

The primeval Phrygians call me Pessinuntica, Mother of the

gods; the Athenians, sprung from their own soil, call me Cecropian Artemis;

for the islanders of Cyprus I am Paphian Aphrodite; for the archers of Crete

I am Dictynna; for the trilingual Sicilians, Stygian Proserpine; and for

the Eleusinians their ancient Mother of the Corn.

”Some know me as Juno, some as Bellona of the Battles; others as

Hecate, others again as Rhamnubia, but both races of Ethiopians, whose lands

the morning sun first shines upon, and the Egyptians who excel in ancient

learning and worship me with ceremonies proper to my godhead, call me by

my true name, namely, Queen Isis.”’

WALSH'S TRANSLATION (1994) pp. 218-221

‘A sudden fear aroused me at about the first watch of

the night. At that moment I beheld the full moon rising from the sea-waves,

and gleaming with special brightness. In my enjoyment of the hushed isolation

of the shadowy night, I became aware that the supreme goddess wielded her

power with exceeding majesty, that human affairs were controlled wholly by

her provinces, that the world of cattle and wild beasts and even things inanimate

were lent vigour by the divine impulse of her light and power; that the

bodies of earth, sea, and sky now increased at her waxing, and now diminished

in deference to her waning. It seemed that Fate had now had her fill of

my grievous misfortunes, and was offering hope of deliverance, however delayed.

So I decided to address a prayer to the venerable image of the goddess appearing

before my eyes. I hastily shook off my torpid drowsiness, and sprang up,

exultant and eager. I was keen to purify myself at once, so I bathed myself

in the sea-waters, plunging my head seven times beneath the waves, for Pythagoras

of godlike fame proclaimed that number to be especially efficacious in sacred

rites. Then with tears in my eyes I addressed this prayer to the supremely

powerful goddess:

“Queen of heaven, at one time you appear in the guise of

Ceres, bountiful and primeval bearer of crops. In your delight at recovering

your daughter, you dispensed with the ancient, barbaric diet of acorns and

schooled us in civilized fare; now you dwell in the fields of Eleusis. At

another time you are heavenly Venus; in giving birth to Love when the world

was first begun, you united the opposite sexes and multiplied the human race

by producing ever abundant offspring; now you are venerated at the wave-lapped

shrines of Paphos. At another time you are Phoebus’ sister; by applying soothing

remedies you relieve the pain of child-birth, and have brought teeming numbers

to birth; now you are worshipped in the famed shrines of Ephesus. At another

time you are Proserpina, whose howls at night inspire dread, and whose triple

form restrains the emergence of ghosts as you keep the entrance to earth above

firmly barred. You wander through diverse groves, and are appeased by varying

rites. With this feminine light of yours you brighten every city and nourish

the luxuriant seeds with your moist fire, bestowing your light intermittently

according to the wandering paths of the sun. But by whatever name or rite

or image it is right to invoke you, come to my aid at this time of extreme

privation, lend stability to my disintegrating fortunes, grant respite and

peace to the harsh afflictions which I have endured. Let his be the full

measure of my toils and hazards; rid me of this grisly, four-footed form.

Restore me to the sight of my kin; make me again the Lucius that I was. But

if I have offended some deity who continues to oppress me with implacable

savagery, at least allow me to die, since I cannot continue to live.”

These were the prayers which I poured out, supporting them

with cries of lamentation. But then sleep enveloped and overpowered my wasting

spirit as I lay on that couch of sand. But scarcely had I closed my eyes

when suddenly from the midst of the sea a divine figure arose, revealing features

worthy of veneration even by the gods. Then gradually the gleaming form seemed

to stand before me in full figure as she shook off the sea-water. I shall

try to acquaint you too with the detail of her wondrous appearance, if only

the poverty of human speech grants me powers of description, or the deity

herself endows me with a rich feast of eloquent utterance.

To begin with, she had a full head of hair which hung down,

gradually curling as it spread loosely and flowed gently over her divine

neck. Her lofty head was encircled by a garland interwoven with diverse blossoms,

at the centre of which above her brow was a flat disk resembling a mirror,

or rather the orb of the moon, which emitted a glittering light. The crown

was held in place by coils of rearing snakes on right and left, and it was

adorned above with waving ears of corn. She wore a multi-coloured dress woven

from fine linen, one part of which shone radiantly white, a second glowed

yellow with saffron blossom, and a third blazed rosy red. But what rivetd

my eyes above all else was her jet-black cloak, which gleamed with a dark

sheen as it enveloped her. It ran beneath her right arm across to her left

shoulder, its fringe partially descending in the form of a knot. The garment

hung down in layers of successive folds, its lower edge gracefully undulating

with tasselled fringes.

Stars glittered here and there along its woven border and

on its flat surface, and in their midst a full moon exhaled fiery flames.

Wherever the hem of that magnificent cloak billowed out, a garland composed

of every flower and every fruit was inseparably attached to it. The goddess’s

appurtenances were extremely diverse. In her right hand she carried a bronze

rattle; it consisted of a narrow metal strip curved like a belt, through

the middle of which were passed a few rods; when she shook the rattle vigorously

three times with her arm, the rods gave out a shrill sound. From her left

hand dangled a boat-shaped vessel, on the handle of which was the figure of

a serpent in relief, rearing high its head and swelling its broad neck. Her

feet, divinely white, were shod in sandals fashioned from the leaves of a

palm of victory. Such, then, was the appearance of the mighty goddess. She

breathed forth the fertile fragrance of Arabia as she deigned to address me

in words divine:

“Here I am, Lucius, roused by your prayers. I am the mother

of the world of nature, mistress of all the elements, first-born in this

realm of time. I am the loftiest of deities, queen of departed spirits, foremost

of heavenly dwellers, the single embodiment of all gods and goddesses. I

order with my nod the luminous heights of heaven, the healthy sea-breezes,

the sad silences of the infernal dwellers. The whole world worships this single

godhead under a variety of shapes and liturgies and titles. In one land the

Phrygians, first-born of men, hail me as the Pessinuntian mother of the gods;

elsewhere the native dwellers of Attica call me Cecropian Minerva; the Cretan

archers, the Dictynna Diana; the trilingual Sicilians, Ortygian Proserpina;

the Eleusinians, the ancient goddess Ceres; some call me Juno, other Bellona,

other Hecate, and others still Rhamnusia. But the peoples on whom the rising

sun-god shines with his first rays—eastern and western Ethiopians, and the

Egyptians who flourish with their time-honoured learning—worship me with

the liturgy that is my own, and call me by my true name, which is queen Isis.”‘

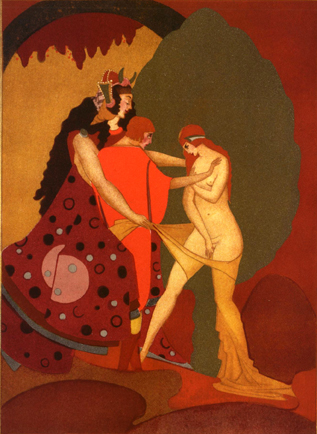

The distraught woman is succoured

-

illustration by

Jean de Bosschère

|

KENNEY'S TRANSLATION (1998) pp. 195-198

‘It was not yet midnight when I awoke with a sudden start to see the full

moon just rising from the sea-waves and shining with unusual brilliance.

Now, in the silent secrecy of night, was my opportunity. Knowing that his

greatest of goddesses was supremely powerful; that all human life was ruled

by her Providence; that not only all animals, both tame and wild, but even

lifeless things were animated by the divine power of her light and might;

that as she waxed and waned, so in sympathy and obedience every creature

on earth or in the heavens or in the sea was increased or diminished; and

seeing that Fate was now seemingly satiated with my long tale of suffering

and was offering me a hope, however late in the day, of rescue: I decided

to beg for mercy from the awesome manifestation of the goddess that I now

beheld. At once, shaking off my sluggish repose, I jumped up happily and

briskly, and eager to purify myself I plunged into the sea. Seven times I

immersed my head, since that is the number which the godlike Pythagoras has

told us is most appropriate in religious rituals, and then weeping I uttered

my silent prayer to the all-powerful goddess.

“Queen of heaven, whether you are Ceres, nurturing mother and creatrix

of crops, who in your joy at finding your daughter again set aside the ancient

acorn, fodder for wild beasts, and taught man the use of civilized food,

and now fructify the ploughlands of Eleusis; or whether you are Venus Urania,

who in the first beginnings of the world by giving birth to Love brought

together the opposite sexes and so with never-ending regeneration perpetuated

the human race, and now are worshipped in the sanctuary of sea-girt Paphos;

or whether you are Phoebus’ sister, who by relieving women in labour with

your soothing remedies have raised up many peoples, and now are venerated

in your shrine at Ephesus; or whether you are Proserpine of the fearful night-howling

and triple countenance, you who hold back the attacks of ghosts and control

the gates of hell, who pass at will among the sacred groves and are propitiated

with many different rites; you who brighten cities everywhere with your female

light and nourish the fertile seeds with your moist warmth and dispense according

to the motions of the Sun an ever-changing radiance; by whatever name, in

whatever manner, in whatever guise it is permitted to call on you: do you

now at last help me in this extremity of tribulation, do you rebuild the

wreck of my fortunes, do you grant peace and respite from the cruel misfortunes

that I have endured: let there be an end of toils, an end of perils. Banish

this loathsome animal shape, return me to the sight of my friends and family,

restore Lucius to himself; or if I have offended some power that still pursues

me with its savagery and will not be appeased, then at last let me die if

I may not live.”

Such were the prayers that I poured forth, accompanied with

pitiful lamentations; then sleep once more enveloped my fainting senses and

overcame me in the same resting place as before. I had scarcely closed my

eyes when out of the sea there emerged the head of the goddess, turning on

me that face revered even by the gods; then her radiant likeness seemed by

degree to take shape in its entirety and stand, shaking off the brine, before

my eyes. Let me try to convey to you too the wonderful sight that she presented,

that is if the poverty of human language will afford me the means of doing

so or the goddess herself will furnish me with superabundance of expressive

eloquence.

First, her hair: long, abundant, and gently curling, it fell

caressingly in spreading waves over her divine neck and builders. Her head

was crowned with a diadem variegated with many different flowers; in its

centre, above her forehead, a disc like a mirror or rather an image of the

moon shone with a white radiance. This was flanked on either side by a viper

rising sinuously erect; and over all was a wreath of ears of corn. Her dress

was of all colours, woven of the finest linen, now brilliant white, now saffron

yellow, now a flaming rose-red. But what above all made me stare and stare

again was her mantle. This was jet-black and shone with a dark resplendence;

it passed right round her, under her right arm and up to her left shoulder,

where it was bunched and hung down in a series of many folds to the tasselled

fringes of its surface shone a scattered pattern of stars, and in the middle

of them the full moon radiated flames of fire. Around the circumference of

this splendid garment there ran one continuous garland all made up of flowers

and fruits. Quite different were the symbols that she held. In her right

hand was a bronze sistrum, a narrow strip of metal curved back on itself like

a sword-belt and pierced by a number of thin rods, which when shaken in triple

time gave off a rattling sound. From her left hand hung a gold pitcher, the

upper part of its handle in the form of a rampant asp with head held aloft

and neck puffed out. Her ambrosial feet were shod with sandals woven from

palm-leaves, the sign of victory. In this awesome shape the goddess, wafting

over me all the blessed perfumes of Arabia, deigned to answer me in her own

voice.

“I come, Lucius, moved by your entreaties: I, mother of the

universe, mistress of all the elements, first-born of the ages, highest of

the gods, queen of the shades, first of those who dwell in heaven, representing

in one shape all gods and goddesses. My will controls the shining heights

of heaven, the health-giving sea-winds, and the mournful silences of hell;

the entire world worships my single godhead in a thousand gods; the native

Athenians the Cecropian Minerva; the island-dwelling Cypriots Paphian Venus;

the archer Cretans Dictynnan Diana; the triple-tongued Sicilians Stygian

Proserpine; the ancient Eleusinians Actaean Ceres; some call me Juno, some

Bellona, those on whom the rising and those on whom the setting sun shines,

and the Egyptians who excel in ancient learning, honour me with the worship

which is truly mine and call me by my true name: Queen Isis.”’

|

BOHN'S LIBRARY TRANSLATION (1902)

pp. 220-226

‘Awaking in sudden alarm about the first watch of the night, I beheld

the full orb of the moon shining with remarkable brightness, and just

then emerging from the waves of the sea. Availing myself, therefore, of

the silence and solitude of the night, as I was also well aware that the

great primal goddess possessed a transcendent majesty, and that human affairs

are entirely governed by her providence; and that not only cattle and

wild beasts, but likewise things inanimate, are invigorated by the divine

influence of her light; that the bodies likewise which are on earth, in

the heavens, and in the ea, at one time increase with her increments, and

at another lessen duly with her wanings; being well assured of this, I determined

to implore the august image of the goddess then present, Fate, as I supposed,

being now satiated with my many and great calamities, and holding out to

me at last some prospect of relief.

Shaking off all drowsiness, therefore, I rose with

alacrity, and directly, with the intentio of purifying myself, began bathing

in the sea. Having dipped my head seven times in the waves, because, according

to the divine Pythagoras, that number is especially adapted to religious

purposes, I joyously and with alacrity thus supplicated with a tearful

countenance the transcendently powerful Goddess:—

“Queen of heaven, whether thou art the genial Ceres,

the prime parent of fruits, who, joyous at the discovery of thy daughter,

didst banish the savage nutriment of the ancient acorn, and pointing

out a better food, dost now till the Eleusinian soil; or whether thou

art celestial Venus, who, in the first origin of things, didst associate

the different sexes, through the creation of mutual love, and having propagated

an eternal offspring in the human race, art now worshipped in the sea-girt

shrine of Paphos; or whether thou art the sister of Phoebus, who, by relieving

the pangs of women in travail by soothing remedise, hast brought into the

world multitudes so innumerable, and art now venerated, in the far-famed

shrines of Ephesus; or whether thou art Proserpine, terrific with midnight

howlings, with triple features checking the attack of the ghosts, closing

the recesses of the earth, and who wandering over many a grove, art propitiated

by the various modes of worship; with that feminine brightness of thine,

illuminating the walls of every city, and with thy vaporous beams nurturing

the joyous seeds of plants, and for the revolutions of the sun ministering

thy fitful gleams: by whatever name, by whatever ceremonies, and under whatever

form it is lawful to invoke thee; do thou graciously succour me in this

my extreme distress, support my fallen fortunes, and grant me rest and peace,

after the endurance of so many sad calamities. Let there be an end of my

sufferings, let there be an end of my perils. Remove from me the dire form

of a quadruped, restore me to the sight of my kindred, restore me to Lucius,

my former self. But if any offended deity pursues me with inexorable cruelty,

may it at least be allowed me to die, if it is not allowed me to live.”

Having after this manner poured forth my prayers

and added bitter lamentations, sleep again overpowered my stricken feeling

on the same bed. Scarcely had I closed my eyes, when behold! a divine

form emerged from the middle of the sea, and disclosed features that even

the gods themselves might venerate. After this, by degrees, the vision,

resplendent throughout the whole body, seemed gradually to take its stand

before me, rising above the surface of the sea. I will even make an attempt

to describe to you its wondrous appearance, if, indeed, the poverty of

human language will afford me the power of appropriately setting it forth;

or, if the Divinity herself will supply me with a sufficient stock of eloquent

diction.

In the first place, then, her hair, long and hanging

in tapered ringlets, fell luxuriantly on her divine neck; a crown of

varied form encircled the summit of her head, with a diversity of flowers,

and in the middle of it, just over her forehead, there was a flat circlet,

which resembled a mirror, or rather emitted a white refulgent light, thus

indicating that she was the moon. Vipers rising from furrows of the earth,

supported this on the right hand and on the left, while ears of corn projected

on either side. Her garment was of many colours, woven of fine flax; in

one part it was resplendent with a clear white colour, in another it was

yellow like the blooming crocus, and in another flaming with a rosy redness.

And then, what rivetted my gaze far more than all, was her mantle of the deepest

black, that shone with a glossy lustre. It was wrapped around her, and passing

from below her right side over the left shoulder, was fastened in a knot

that resembled the boss of a shield, while a part of the robe fell down in

many folds, and gracefully floated with its little knots of fringe that

edged its extremities. Glittering stars were dispersed along the embroidered

extremities of the robe, and over its whole surface; and in the middle

of them a moon of two weeks old breathed forth its flaming fires. Besides

this, a garland, wholly consisting of flowers and fruits of every kind,

adhered naturally to the border of this beautiful mantle, in whatever direction

it was wafted by the breeze.

The objects she carried in her hands were of a different

description. In her right hand she bore a brazen sistrum, through the

narrow rim of which, winding just like a girdle for the body, passed a

few little rods, producing a sharp shrill sound, while her arm imparted

motion to the triple chords. An oblong vessel, made of gold, in the shape

of a boat, hung down from her left hand, on the handle of which, in that

part in which it met the eye, was an asp raising its head erect, and with

its throat puffed out on either side. Shoes, too, woven from the palm,

the emblem of victory, covered her ambrosial feet.

Such was the appearance of the mighty goddess,

as, breathing forth the fragrant perfumes of Arabia the happy, she deigned

with her divine voice thus to address me: “Behold me, Lucius; moved by

thy prayers, I appear to thee; I, who am Nature, the parent of all things,

the mistress of all the elements, the primordial offspring of time, the

supreme among Divinities, the queen of departed spirits, the first of the

celestials, and the uniform manifestation of the Gods and Goddesses; who

govern by my nod the luminous heights of heaven, the salubrious breezes

of the ocean, and the anguished silent realms of the shades below: whose

one sole divinity the whole orb of the earth venerates under a manifold form,

with different rites, and under a variety of appellations. Hence the Phrygians,

that primæval race, call me Pessinuntica, the Mother of the Gods;

the Aborigines of Attica, Cecropian Minerva; the Cyprians, in their sea-girt

isle, Paphian Venus; the arrow-bearing Cretans, Diana Dictynna; the three-tongued

Sicilians, Stygian Proserpine; and the Eleusinians, the ancient Goddess

Ceres. Some call me Juno, other Bellona, other Hecate, and others Rhamnusia.

But those who are illuminated by the earliest rays of that divinity, the

Sun, when he rises, the Æthopians, the Arii, and the Egyptians, so

skilled in ancient learning, worshipping me with ceremonies quite appropriate,

call me by my true name, Queen Isis…‘

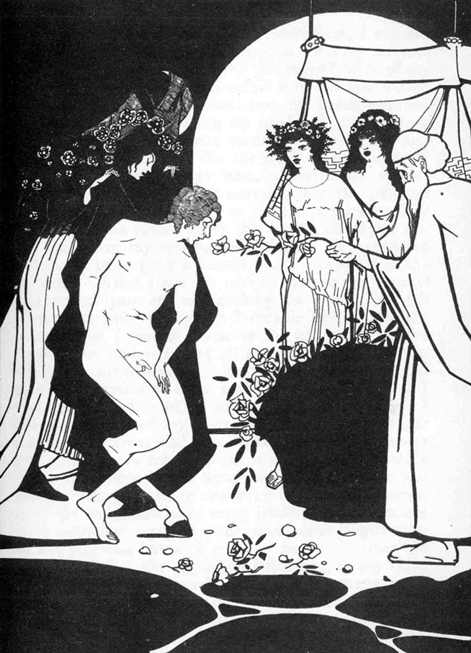

Lucius restored to human shape

by the Grace of Isis -

illustration by Jean

de Bosschère

|

ADLINGTON TRANSLATION (1639)

pp. 261-264

‘When midnight came that I had slept my first sleepe, I awaked with

suddaine feare, and saw the Moone shining bright, as when shee is at

the full, and seeming as though she leaped out of the Sea. Then thought

I with my selfe, that that was the most secret time, when the goddesse

Ceres had most puissance and force, considering that all humane things

be governed by her providence: and not onely all beasts private and tame,

but also all wild and savage beasts be under her protection. And considering

that all bodies in the heavens, the earth and the seas, be by her increasing

motions increased, and by her diminishing motions diminished: as weary of

all my cruell fortune and calamity, I found good hope and soveraigne remedy,

though it were very late, to be delivered from all my misery, by invocation

and prayer, to the excellent beauty of the Goddesse, whom I saw shining before

mine eyes, wherefore shaking off mine Assie and drowsie sleepe, I arose

with a joyfull face, and mooved by a great affection to purifie my selfe,

I plunged my selfe seven times into the water of the Sea, which number of

seven is conveniable and agreeable to holy and divine things, as the worthy

and sage Philosopher Pythagoras hath declared. Then with a weeping countenance,

I made this Orison to the puissant Goddesse, saying: O blessed Queene of

heaven, whether thou be the Dame Ceres which art the originall and motherly

nource of all fruitfull things in earth, who after the finding of thy daughter

Proserpina, through the great joy which thou diddest presently conceive,

madest barraine and unfruitfull ground to be plowed and sowne, and now thou

inhabitest in the land of Eleusie; or whether thou be the celestiall Venus,

who in the beginning of the world diddest couple together all kind of things

with an ingendered love, by an eternall propagation of humane kind, art now

worshipped within the Temples of the Ile Paphos, thou which art the sister

of the God Phœbus, who nourishest so many people by the generation of beasts,

and art now adored at the sacred places of Ephesus, thou which art horrible

Proserpina, by reason of the deadly howlings which thou yeeldest, thou hast

the power to stoppe and put away the invasion of the hags and Ghoasts which

appeare unto men, and to keepe them downe in the closures of the earth: thou

which nourishest all the fruits of the world by thy vigor and force; with

whatsoever name or fashion it is lawfull to call upon thee, I pray thee,

to end my great travaile and misery, and deliver mee from the wretched fortune,

which had so long time pursued me. Grant peace and rest if it please thee

to my adversities, for I have endured too too [sic] much labour and perill.

Remoove from me my shape of mine Asse, and render to me my pristine estate,

and if I have offended in any point of divine Majesty, let me rather dye

then live, for I am full weary of life.

|

When I had ended this orison, and discovered my plaints

to the Goddesse, I fortuned to fall asleepe, and by and by appeared unto

me a divine and venerable face, worshipped even of the Gods themselves.

Then by little and little I seemed to see the whole figure of her body,

mounting out of the sea and standing before mee, wherefore I purpose to

describe her divine semblance, if the poverty of my humane speech will suffer

me, or her divine power give me eloquence thereto. First shee had a great

abundance of haire, dispersed and scattered about her neck, on the crowne

of her head she bare many garlands enterlaced with floures, in the middle

of her forehead was a compasse in fashion of a glasse, or resembling the

light of the Moone, in one of her hands she bare serpents, in the other,

blades of corne, her vestiment was of fine silke yeelding divers colours,

sometime yellow, sometime rosie, sometime flamy, and sometime (which troubled

my spirit sore) darke and obscure, covered with a blacke robe in manner

of a shield, and pleated in most subtill fashion at the skirts of her

garments, the welts appeared comely, whereas here and there the starres

glimpsed, and in the middle of them was placed the Moone, which shone

like a flame of fire, round about the robe was a coronet or garland made

with flowers and fruits. In her right hand shee had a timbrell of brasse,

which gave a pleasant sound, in her left hand shee bare a cup of gold, out

of the mouth whereof the serpent Aspis lifted up his head, with a swelling

throat, her odoriferous feete were covered with shoes interlaced and wrought

with victorious palme. Thus the divine shape breathing out the pleasant

spice of fertill Arabia, disdained not with her divine voyce to utter these

words unto me: Behold Lucius I am come, thy weeping and prayers hath mooved

mee to succour thee. I am she that is the naturall mother of all things,

mistresse and governesse of all the Elements, the initiall progeny of worlds,

chiefe of powers divine, Queene of heaven, the principall of the Gods celestiall,

the light of the goddesses: at my will the planets of the ayre, the wholesome

winds of the Seas, and the silences of hell be disposed; my name, my divinity

is adored throughout all the world in divers manners, in variable customes

and in many names, for the Phrygians call me the mother of the Gods: the

Athenians, Minerva: the Cyprians, Venus: the Candians, Diana: the Sicilians

Proserpina: the Eleusians, Ceres: some Juno, other Bellona, other Hecate:

and principally the æthiopians which dwell in the Orient, and the

ægyptians which are excellent in all kind of ancient doctrine, and

by their proper ceremonies accustome to worship mee, doe call mee Queene

Isis…’

Compare this episode with Krishna’s revelation

of his godhood to Arjuna in the Hindu

Bhagavad-Gita

:

‘Krishna said: “I am the Soul dwelling in the heart

of everything. I am the Beginning, the Middle and the End. Of the Adityas

I am Vishnu. Of the lights I am the sun. Among the stars I am the moon.

Of the Vedas I am the Sama. Of the senses I am the mind and in the living

beings I am the intellect. Of the Rudras I am Sankara. Of the mountains I

am Meru. Of words, I am the great AUM. Of the weapons, I am the thunderbolt.

Of those that measure I am Time. I am Death that destroys all and I am the

origin of things that are yet to be born. The germ of all living beings is

Myself. There is nothing moving or unmoving that can exist without Me. Anything

endowed with grandeur, with beauty, with strength, has sprung only from a

spark of My splendour. I stand pervading the universe with a single fragment

of Me.’

Krishna granted [Arjuna] divine eyes and revealed to [him] His

Divine Form. Like the light of a thousand suns, the splendour of the Mighty

One was seen by Arjuna. He beheld the entire universe with all its myriad

manifestations all gathered together in one. He bowed his head to the Lord.

Pressing his palms together in incessant salutation he said: “Lord of Lords!

In Thy body I see all the gods and all the varied hosts of beings as well.

I see Brahma and all the rishis. You are infinite in form. There is no beginning

or middle or end. You are a glowing mass of light. You are the Imperishable,

the Supreme that has to be realised. You are the home of this entire Universe.

You are the Guardian of the Eternal law. You are the Primal Being. Your

eyes are the sun and moon, and Your face is glowing with the radiance of

fire, and this universe is being devoured by the fire that is You. By Thee

are filled the interspaces of heaven and earth and the sky. Looking on you,

the world trembles and so do I.’ (The Mahabharata , Bhishma

Parva , Chap. XLIX, Book 6 [Subramaniam pp.432-433])