‘There was once a hard-up labouring-man who lived a pinched

life on his wage as a journeyman-carpenter. He had a wifie as poor as himself,

a little slip of a thing but (so scandal had it) incurably lecherous. One

day when the carpenter had gone off to his work after breakfast, the wife’s

lover sidled warily into the house. But while the adulterers were amorously

parleying together and imagining themselves quite secure, the complaisant

husband (without any suspicion of what was going on) unexpected returned.

Finding the doors locked and bolted, he thought nothing but praise for

his wife’s careful chastity; and he knocked and whistled to announce his

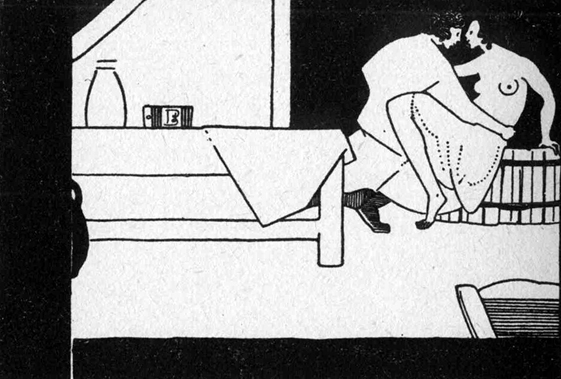

arrival. The cunning wife, well-schooled in all naughty guiles, at once

loosed her lover from her serpenting embraces and secreted him in an old

empty tub that was half-sunk in a corner of the room. Then, throwing open

the door, she ushered-in her husband with a nagging welcome.

”So you’ve come back empty-handed,” she cried, “a gentleman of leisure with your arms folded! What are we to live on if you can’t keep a job? Where’s the food coming from, I’d like to know? Here I am, wearing myself away, day and night, with twirling on my spindle, or there wouldn’t be even a lamp to give us a drop of light in our pokey room. Ah, how much happier is my nextdoor neighbour Daphne who wallows in food, drink, and fornication, from early morning to bedtime.”

”What’s all this noise about?” answered the abused husband. ”Although the foreman gave us a holiday, being called into town on some market-business, yet I drove a bargain myself to make sure of a sup tonight. Do you see that old tub? It’s no use, and it takes up such a great deal of space that it’s only a stumbling-block and nuisance in our little shanty. Well, I sold it to a fellow for fivepence. He’ll be here in a moment to pay me and cart it away. So tuck up your skirts and lend me a hand.” “A fine husband!” she exclaimed. ”And what a business-head he has. Why, he’s gone and sold at such a low price the very article that I (only a woman of course) just sold for sevenpence without setting foot out-of-doors.’

Delighted to hear of the extra-tuppence, “Who is it”, asked the husband, “that paid so high for it?”

”So you’ve come back empty-handed,” she cried, “a gentleman of leisure with your arms folded! What are we to live on if you can’t keep a job? Where’s the food coming from, I’d like to know? Here I am, wearing myself away, day and night, with twirling on my spindle, or there wouldn’t be even a lamp to give us a drop of light in our pokey room. Ah, how much happier is my nextdoor neighbour Daphne who wallows in food, drink, and fornication, from early morning to bedtime.”

”What’s all this noise about?” answered the abused husband. ”Although the foreman gave us a holiday, being called into town on some market-business, yet I drove a bargain myself to make sure of a sup tonight. Do you see that old tub? It’s no use, and it takes up such a great deal of space that it’s only a stumbling-block and nuisance in our little shanty. Well, I sold it to a fellow for fivepence. He’ll be here in a moment to pay me and cart it away. So tuck up your skirts and lend me a hand.” “A fine husband!” she exclaimed. ”And what a business-head he has. Why, he’s gone and sold at such a low price the very article that I (only a woman of course) just sold for sevenpence without setting foot out-of-doors.’

Delighted to hear of the extra-tuppence, “Who is it”, asked the husband, “that paid so high for it?”

GRAVE'S TRANSLATION (1950) pp. 196-198

‘This man depended for his livelihood on his small earnings

as a jobbing smith, and his wife had no property either but was famous for

her sexual appetite. One morning early, as soon as he had gone off to work,

an impudent lover of his wife’s slipped into the house and was soon tucked

up in bed with her. The unsuspecting smith happened to return while they

were still hard at work. Finding his door locked and barred he nodded approval—how

chaste his wife must be to take such careful precautions against any intrusions

on her privacy! Then he whistled under the window, in his usual way, to announce

his return. She was a resourceful woman and, disengaging her lover from

a particularly tight embrace, hid him in a big tub that stood in the corner

of the room. It was dirty and rotten, but quite empty. Then she opened the

door and began scolding: “You lazy fellow, strolling back as usual with folded

arms and nothing in your pockets! When are you going to start working for

your living and bring us home something to eat? What about me, eh? Here I

sit every day from dawn to dusk at my spinning wheel, working my fingers

to the bone and earning only just enough to keep oil in the lamp. What a miserable

hole this is, too! I only wish I were my friend Daphne: she can eat and drink

all day long and take as many lovers as she pleases.”

‘Hey, what’s all this?” cried the smith, his feelings injured. “What fault of mine is it if the contractor has to spend the day in court and lays us off until tomorrow? And it isn’t as though I hadn’t thought about our dinner: you see that useless old tub cluttering up our place? I have just sold it to a man for five drachmae. He’ll be here soon to put down the money and carry it away. So lend me a hand will you? I want to move it outside for him.”

She was not in the least disconcerted, and quickly thought of a plan for lulling any suspicions he might have. She laughed rudely: “What a wonderful husband I have, to be sure! And what a good nose he has for a bargain! He goes out and sells our tub for five drachmae. I’m only a woman, but I have already sold it for seven without even setting foot outside the house.’

He was delighted. “Who on earth gave you such a good place?”

“Hush, you idiot,” she said. “He’s still down inside the thing, having a good look to see whether it’s sound.”

The lover took his cue from her at once. He bobbed up and said: “I’ll tell you what, ma’am, your tub is very old and seems to be cracked in scores of places.” Then he turned to the smith: “I don’t know who you are, little man, but I should be much obliged for a candle. I must scrape the inside and see whether it’s the sort of article I need. I haven’t any money to throw away; it doesn’t grow on apple-trees these days, does it?”

So the simple-minded smith lighted a candle without delay and said: “No, no, mate, don’t put yourself to so much trouble. You stand by while I give the tub a good clean-up for you.”

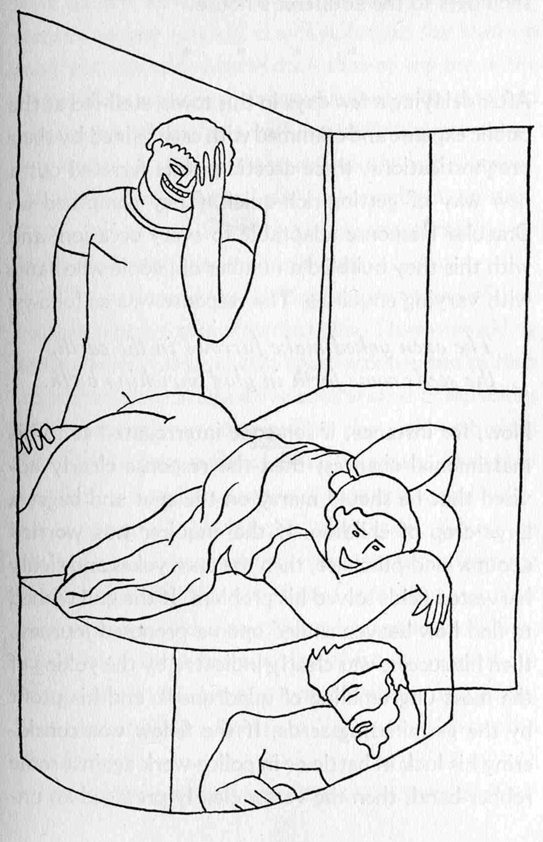

He peeled off his tunic, took the candle, lifted up the tub, turned it bottom upwards, then got inside and began working away busily.

The eager lover at once lifted up the smith’s wife, laid her on the tub bottom upwards above her husband’s head and followed his example. She greatly enjoyed the situation, like the whore she was. With her head hanging back over the side of the tub she directed the work by laying her finger on various spots in turn with: “Here, darling, here!…Now there…” until both jobs were finished to her satisfaction. The smith was paid seven drachmae, but had to carry the tub on his own back to the lover’s lodgings.’

‘Hey, what’s all this?” cried the smith, his feelings injured. “What fault of mine is it if the contractor has to spend the day in court and lays us off until tomorrow? And it isn’t as though I hadn’t thought about our dinner: you see that useless old tub cluttering up our place? I have just sold it to a man for five drachmae. He’ll be here soon to put down the money and carry it away. So lend me a hand will you? I want to move it outside for him.”

She was not in the least disconcerted, and quickly thought of a plan for lulling any suspicions he might have. She laughed rudely: “What a wonderful husband I have, to be sure! And what a good nose he has for a bargain! He goes out and sells our tub for five drachmae. I’m only a woman, but I have already sold it for seven without even setting foot outside the house.’

He was delighted. “Who on earth gave you such a good place?”

“Hush, you idiot,” she said. “He’s still down inside the thing, having a good look to see whether it’s sound.”

The lover took his cue from her at once. He bobbed up and said: “I’ll tell you what, ma’am, your tub is very old and seems to be cracked in scores of places.” Then he turned to the smith: “I don’t know who you are, little man, but I should be much obliged for a candle. I must scrape the inside and see whether it’s the sort of article I need. I haven’t any money to throw away; it doesn’t grow on apple-trees these days, does it?”

So the simple-minded smith lighted a candle without delay and said: “No, no, mate, don’t put yourself to so much trouble. You stand by while I give the tub a good clean-up for you.”

He peeled off his tunic, took the candle, lifted up the tub, turned it bottom upwards, then got inside and began working away busily.

The eager lover at once lifted up the smith’s wife, laid her on the tub bottom upwards above her husband’s head and followed his example. She greatly enjoyed the situation, like the whore she was. With her head hanging back over the side of the tub she directed the work by laying her finger on various spots in turn with: “Here, darling, here!…Now there…” until both jobs were finished to her satisfaction. The smith was paid seven drachmae, but had to carry the tub on his own back to the lover’s lodgings.’

‘This man was extremely poor; he made his living by hiring himself out as a day-labourer at very low wages. He had a wife, as poor as himself, but notorious for her outrageously immoral behaviour. One day, directly he had left early for the job he had in hand, there quietly slipped into the house her dashing blade of a lover. While they were busily engaged with each other, no holds barred, and not expecting visitors, the husband, quite unaware of the situation, and not suspecting anything of the kind, unexpectedly came back. Finding the door closed and locked he commended his wife’s virtue, and knocked, whistling to identify himself. The cunning baggage, who was past mistress in goings-on of this kind, disentangled her lover from her tight embraces and quietly ensconced him in an empty storage-jar which stood half hidden in a corner. Then she opened the door, and before her husband was well inside she greeted him acidly. “So,” said she, “I’m to watch you strolling about idly, doing nothing and with your hands in your pockets instead of going to work as usual and seeing about getting us something to live on and buy food with? Here am I wearing my fingers to the bone night and day with spinning wool, just to keep a light burning in our hovel! Don’t I wish I was Daphne next door, rolling about in bed with her lovers and already tight by breakfast-time!”

Her husband was put out. “What’s all that for?” he asked. “The boss has got to be in court, so he’s given us the day off; but I have done something about today’s dinner. You know that jar that never has anything in it and takes up space uselessly – doing nothing in fact but get in our way? I’ve just sold it to a man for six denarii, and he’s coming to pay up and collect his property. So how about some action and lending me a hand for a minute to rout it out and hand it over?” The crafty minx was quite equal to this and shrieked with laughter. “Some husband I’ve got! Some bargainer! He’s disposed of it for six, and I, a mere woman, I’ve already sold it for seven without even leaving the house!” Her husband was delighted by the increased price. “Where is this chap who’s made such a good offer?” he asked. “He’s inside it, stupid,” she answered, “giving it a good going-over to see if it’s sound.”

Her lover did not miss his cue. Emerging at once, “If you want me to be frank, ma’am,” he said, “that jar of yours is pretty antique, and there are yawning cracks all over it”; and turning to the husband as if he had no idea who he was, “Come on, chum, whoever you are, get cracking and fetch me a light so I can scrape away all the inside dirst and see if the thing’s fit to use – money doesn’t grow on trees, you know.” Her admirable husband, sharp fellow, suspected nothing, and at once lighted a lamp. “Come out, old man,” he said. “Sit down and make yourself comfortable, and let me get it cleaned out properly for you.” So saying, he stripped and taking the lamp in with him started to scrape the encrusted deposits off the rotten old jar. Meanwhile her smart young gallant made the man’s wife lean face downwards across the jar, and without turning a hair gave her too a good going-over. She lowered her head into the jar and enjoyed herself at her husband’s expense like the clever whore she was, pointing at this place or that or yet another one that needed scouring, until both jobs were finished. Then the unfortunate artisan took his seven denarii and was made to carry the jar himself to the adulterer’s house.‘

BOHN'S LIBRARY TRANSLATION (1902) pp. 170-172

‘There was a poor man who had nothing to subsist on but

his scanty earnings as a journeyman carpenter. He had a wife who was also

very poor, but notorious for her lasciviousness. One day, when the man

had gone out betimes to his work, an impudent gallant immediately stepped

into his house. But whilst he and the wife were warmly engaged, and thinking

themselves, secure, the husband, who had no suspicion of such doings, returned

quite unexpectedly. The door being locked and bolted, for which he mentally

extolled his well-conducted wife, he knocked and whistled to announce his

presence. Then his cunning wife, who was quite expert in such matters, released

the man from her close embraces, and hid him quickly in an old empty butt,

that was sunk half-way into the ground, in a corner of the room. Then she

opened the door, and began to scold her husband the moment he entered. “So

you are come home empty-handed, are you?” said she “to sit here with your

arms folded, doing nothing, instead of going on with your regular work, to

get us a living and buy us a bit food; while I, poor soul, must work my fingers

out of joint, spinning wool day and night, to have at least as much as will

keep a lamp burning in our bit of a room. Ah, how much better off is my neighbour

Daphne, that has her fill of meat and drink from daylight to dark, and enjoys

herself with her lovers.”

“What need of all this fuss?” replied the abused husband; “for though our foreman has given us a holiday, having business of his own in the forum, I have nevertheless provided for our supper to-night. You see that useless butt, that takes up so much room, and is only an incumbrance to our little place; I sold it for five denars to a man who will be here presently to pay for it and take it away. So lend me a hand for a moment, till I get it out to deliver it to the buyer.”

Ready at once with a scheme to fit the occasion, the woman burst into an insolent laugh: “Truly I have got a fine fellow for a husband; a capital hand at a bargain, surely, to go and sell at such a price a thing which I, who am but a woman, had already sold for seven denars, without even quitting the house.”

Delighted at what he had heard, “And who is he,” said the husband, “who has bought it so dear?”

“He has been down in the cask ever so long, you booby,” she replied, “examining it all over to see if it is sound.”

The gallant failed not to take his cue from the woman, and promptly rising up out of the butt, “Shall I tell you the truth, good woman?” he said; “your tub is very old, and cracked in I don’t know how many places.” Then turning to the husband, without appearing to know him: “Why don’t you bring me a light, my tight little fellow, whoever you are, that I may scrape the dirt from the inside, and see whether or not the tub is fit for use, unless you think I don’t come honestly by my money?”

That pattern of all quick-witted husbands, suspecting nothing, immediately lighted a lamp, and said, “Come out, brother, and leave me to make it all right for you.” So saying, he stripped, and taking the lamp with him into the tub, went to work to scrape off the old hardened dirt. And while he was polishing the inside, the charming gallant polished off the carpenter’s wife, laying her on her belly on the outside, she meanwhile amusing herself, like the harlot she was, with making fun of her husband, poking her head into the tub, and pointing out this place and that to be cleaned, and then another, and another; until both jobs being finished, the unfortunate carpenter received his seven denars, and had to carry the butt on his back to the adulterer’s house.’

“What need of all this fuss?” replied the abused husband; “for though our foreman has given us a holiday, having business of his own in the forum, I have nevertheless provided for our supper to-night. You see that useless butt, that takes up so much room, and is only an incumbrance to our little place; I sold it for five denars to a man who will be here presently to pay for it and take it away. So lend me a hand for a moment, till I get it out to deliver it to the buyer.”

Ready at once with a scheme to fit the occasion, the woman burst into an insolent laugh: “Truly I have got a fine fellow for a husband; a capital hand at a bargain, surely, to go and sell at such a price a thing which I, who am but a woman, had already sold for seven denars, without even quitting the house.”

Delighted at what he had heard, “And who is he,” said the husband, “who has bought it so dear?”

“He has been down in the cask ever so long, you booby,” she replied, “examining it all over to see if it is sound.”

The gallant failed not to take his cue from the woman, and promptly rising up out of the butt, “Shall I tell you the truth, good woman?” he said; “your tub is very old, and cracked in I don’t know how many places.” Then turning to the husband, without appearing to know him: “Why don’t you bring me a light, my tight little fellow, whoever you are, that I may scrape the dirt from the inside, and see whether or not the tub is fit for use, unless you think I don’t come honestly by my money?”

That pattern of all quick-witted husbands, suspecting nothing, immediately lighted a lamp, and said, “Come out, brother, and leave me to make it all right for you.” So saying, he stripped, and taking the lamp with him into the tub, went to work to scrape off the old hardened dirt. And while he was polishing the inside, the charming gallant polished off the carpenter’s wife, laying her on her belly on the outside, she meanwhile amusing herself, like the harlot she was, with making fun of her husband, poking her head into the tub, and pointing out this place and that to be cleaned, and then another, and another; until both jobs being finished, the unfortunate carpenter received his seven denars, and had to carry the butt on his back to the adulterer’s house.’